After Tonje, his first wife, is suddenly admitted to the hospital, he leaves her alone there so he can keep a previous engagement with his editor. His sole interest in girls and women lies in how far they will let him go.

Starting around age 16, he habitually binge-drinks until he blacks out, frequently waking up surrounded by blood, vomit, or both. At one point he and a friend set fire to the woods. As a child, he finds amusement in dropping rocks onto cars driving on the highway.

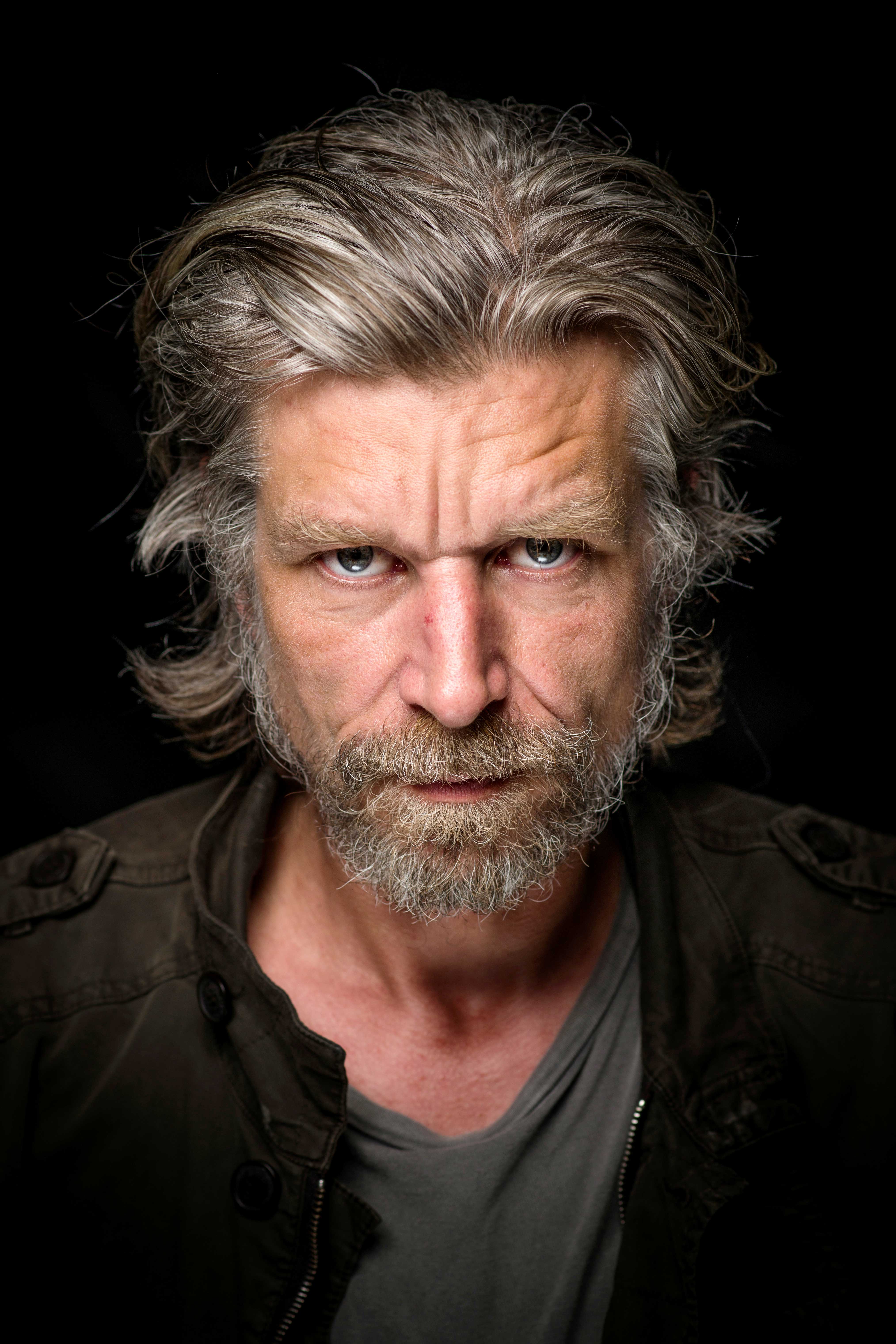

Karl Ove, as he depicts himself-the narrator is explicitly identified with the author-is not an appealing character. Somehow he manages to keep us rooting for his success, even as his disgraces accumulate with the volumes. The fascination of this Brobdingnagian paean to the self, which follows the outline and essence of Knausgaard’s life but fictionalizes scenes and dialogue, lies in watching him fight his way to the creation of himself as a writer-the most important of the “struggles” contained within it. Its 3,600-some pages, at once weirdly self-deprecating and breathtakingly egoistic, began to appear in English, at the rate of a volume a year, in 2012, culminating this fall with the translation of Book Six.

Brutally candid in its banality and sordidness, forsaking conventional strategies of narration and characterization for a heady rush of words on the page, this great disruption of contemporary fiction has sought nothing less than to break the form of the novel. I know all this, as do Knausgaard’s readers around the world, because he has written about it in My Struggle, the massive autobiographical novel that has been the most unlikely international literary sensation of the past decade. To hear more feature stories, see our full list or get the Audm iPhone app.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)